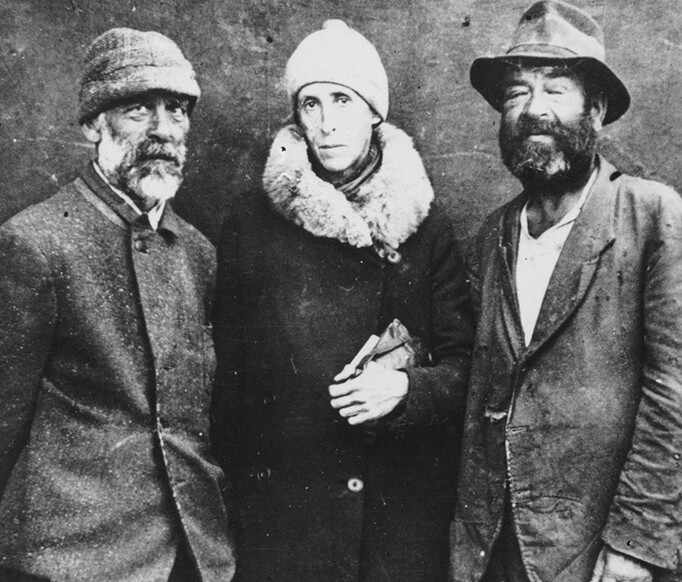

Civilians

|

On the 17th of September 1939 the Soviet Union invaded Poland. The aggressor annexed eastern voivodeships of Poland and began the process of ‘sovietisation’. As part of this process, a decision was made to deport several groups of the population that could have been hostile towards the new power. These actions were taken against a specific group of people, mostly “class enemies’, including ethnic Poles. Today, we can say with certainty that the number of Polish citizens deported deep into the Soviet Union during the Soviet occupation lasting until June 1941 was no less than 330 000.

Most Polish citizens were sent to northern regions of the USSR, to Siberia and Kazakhstan. In the preserved documentation there is no information proving that Uzbekistan was one of the destination of mass deportations of Poles in 1940-1941. Rather, there were individual cases of such phenomenon happening. These people ended up in today’s Uzbekistan not as a result of administrative decisions (typical for deportations), but rather judicial ones - an exile was a sentence. In 1940-1941 around 60 000 Polish citizens were sent to Kolyma.

After the Third Reich attacked the Soviet Union, diplomatic relations between Poland and the USSR have been restored. A bilateral treaty signed on July 30th 1941 enabled Poland to create an army on the territory of the Soviet Union, and obliged Soviet authorities to release all Polish citizens illegally kept in prisons and labour camps. In fulfilling this obligation, the the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR announced the so called amnesty on August 12th 1941. The amnesty allowed Polish citizens to leave prisons, freely move on the USSR territory, and enter Polish Armed Forces in USSR under gen. Władysław Anders’ command (if the physical health and qualifications made it possible). Simultaneously, Polish diplomatic structures were created all across the USSR. Polish delegates gathered also in Uzbekistan (Tashkent and Samardkanda among others). In the framework of Polish Embassy’s actions, they provided assistance to Polish citizens, kept registers, and aided in retrieving documents and looking for relatives.

The desire to leave northern provinces as soon as possible, as well as the news about Polish formations in the south of the USSR, caused Poles to spontanously move towards southern republics, including Uzbekistan. This migration took both the Polish Embassy as well as Soviet authorities (especially NKVD) by surprise. Crowded train stations, where trains evacuating businesses, hundreds of thousands of civilians living nearby front zones and Poles covered by the “amnesty” met, became places of conflicts and a breeding ground for diseases. To alleviate the situation in crowded train stations, NKVD head Ławrientij Beria proposed to resettle around 100 000 Polish citizens to the Uzbek SSR. Local authorities in the republic were not happy with the decision taken in Moscow, as difficulties associated with the resettlement and upkeep of these Poles would become local population’s responsibility. People arriving in Uzbek train stations would find themselves in extreme conditions. Chaos, lack of information, lack of food - all of this forced them to aimlessly wander around train stations (Samarkanda, Boukhara, Tashkent).

Soon after, arriving families were sent to kolkhozes, where harvests have just begun. After the work was done, the situation of Poles deteriorated rapidly. This prompted the Soviet government to evacuate 36 000 Polish citizens to neighbouring Kazakhstan. This was a shock for many Poles, who were therefore forced to go back to places, which they have just left in a hope for a better future. The forced resettlement took place between November 25th and Deecember 5th 1941.

Troops from the Anders’ Army formed yet another group of Polish citizens that moved to Uzbekistan. In January and February 1942 they left their stationing sites (Buzuluk, Chkalov, Tatishchevo) for warmer parts of the Soviet Union (Kazakhstan, Kirgizstan, Uzbekistan). The road south was not easy. Many troops perished, as diseases and difficult living conditions weakened them. The new location of Polish troops did not solve all of the problems. Hot climate and poor sanitary conditions caused an epidemic of contagious diseases.

According to statistics provided by the Polish embassy, 107 655 Polish citizens lived in the Uzbek SSR before Anders’ Army evacuated for Iran. After the evacuation this number dropped to 38 000, as last months of 1942. This number changed constantly, as for some time further Poles covered by the “amnesty” kept arriving, in hopes to be incorporated in the Polish Army and sent to the front. Death was a common sight among the exhausted and malnourished. According to available data over 3 000 Polish troops and civilians perished in Uzbekistan in 1942. Today, this tragedy is commemorated by 17 military cemeteries still existing on the territory of the former Soviet republic.

Not all Polish citizens were lucky enough to evacuate with the Anders’ Army. After the Katyn massacre came to light and diplomatic relations between Poland and USSR broke off once again in 1943, the Association of Polish Patriots took care of the Polish citizens. This was a communist organisation fully controlled by Moscow. It did, however, provide aid to all Polish

citizens, who were left behind in the USSR after the Anders Army’s evacuation. Statistical data about the number of Polish citizens in Uzbekistan at that time is fairly imprecise - in June 1944 it reportedly amounted to 43 400. The Association of Polish Patriots ran Polish schools and orphanages. At the end of 1945, 14 Polish schools were operating in Uzbekistan, attended by over 1 800 pupils. The level of teaching was quite high, and teachers were chosen from personnel loyal to Soviet authorities. Any manifestations of Polish patriotism incompatible with the party line were punished. There were also two Polish kindergartens - in Boukhara and Samarkanda - attended by around 200 pupils.

From the second half of 1944, possibilities of resettling Polish citizens to other republics of the Soviet Union began to appear. In July 1944, approximately 2 000 people left Uzbekistan for Ukraine occupied by the Red Army (although the government allowed the resettlement of 30 000). The significant wave of resettlements began as part of the repatriation, when Polish citizens could return to the post-war territory of Poland. Repatriation from Uzbekistan began in 1945 and ended in 1948. During this action, over 32 000 people returned to their homeland.

To conclude, it is worth pointing out that around 100 000 Polish citizens resided on the territory of Uzbekistan.

Not all of them had the same fate. Some kept fighting for the Polish army, while others worked tirelessly in kolkhozes. One must also remember those, who did not survive the hardships of deportation and remained in Uzbekistan forever. Warm, friendly relations were formed between Poles and Uzbeks - hunger and hard work taught representatives of both nations to support each other and share everything they had with each other.

tel.: +48 58 323 75 20

e-mail: sekretariat@muzeum1939.pl

tel.: + 48 85 672 36 01

e-mail: sekretariat@sybir.bialystok.pl

tel.: +998 78 120 86 51